This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of 'Brain On Fire' by Susannah Cahalan. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

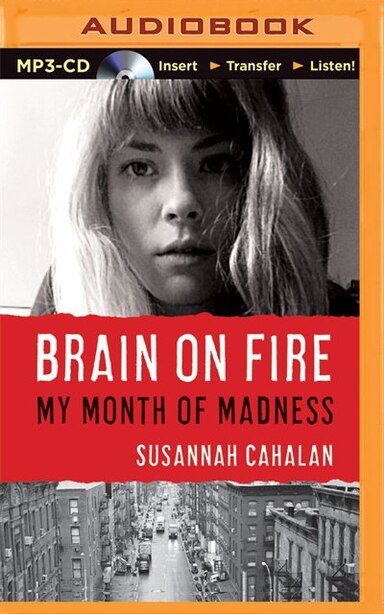

Brain on Fire (2012) is a memoir by New York Post writer Susannah Cahalan that details her struggle with a rare autoimmune disease, anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis. Cahalan recollects the journey through illness that took her from a normal, 24-year-old journalist to a. Learn more about Brain on Fire at Reporter Susannah Cahalan reveals her account of her inexplicable physical and mental breakdown–a. Brain on Fire is the powerful account of one woman's struggle to recapture her identity. When 24-year-old Susannah Cahalan woke up alone in a hospital room, strapped to her bed and unable to move or speak, she had no memory of how she'd gotten there. Susannah cahalan. Home; work; appearances; contact; the great pretender. The great pretender — view — brain on fire — view —. Start studying Brain on Fire - Susannah Cahalan. Learn vocabulary, terms, and more with flashcards, games, and other study tools.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness about? How did Susannah Cahalan put together what happened to her?

Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness tells the story of Susannah Cahalan’s missing month in the hospital. She appeared to have a psychosis, but her brain was attacking itself.

See what happened in Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness.

What Happened in Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness

After twenty-eight days in the hospital, Susannah is discharged. She’ll need an at-home nurse; biweekly visits to the hospital to flush out the antibodies with a plasma exchange; a full-body 3-D scan; and full-time rehab.

Still vastly divorced from her old self, Susannah has little self-awareness when she’s released from the hospital. She makes significant progress over the next few months, but in her own mind, she’s uncertain about herself. For Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, she had to research herself.

Experts are called in to do an assessment. It reveals a divide between Susannah’s internal world and the world around her. Social situations are especially difficult because she’s aware of how strange she appears to the people around her. Susannah often feels that her true self is trying to connect with the world outside but can’t break past her body. She worries that she’s become boring—the most difficult adjustment to a new self she has to make.

Susannah’s old self finally reawakens. She begins reading again and starts keeping a diary. This was the start of Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. Her father encourages her to draw upon her memory, but she can recall only numbness, sleepiness, and three seizures. She remembers nothing from her time in the hospital.

As a result of her illness, Susannah has gained 50 pounds. She obsesses about being fat. Her worries about being fat are actually worries about who she will become: Will she remain as slow as she is now, or will she regain the spark that defines her true nature? When people ask, “How are you?” Susannah recognizes that she no longer knows who “I” is.

Susannah regains former functions and personality traits. She summarizes her experience for Paul, her mentor at the Post, and he certifies that her writing skills have returned.

Paul’s encouragement is all Susannah needs. She begins a program of research and becomes obsessed with understanding how a human body attacks itself. Paul actively encourages Susannah to return to work. On the appointed day, Susannah dresses up and takes a train into the city, but both she and Paul realize it’s too soon for her to return to work.

Two weeks later Susannah gets an assignment from the Post. Her article is published on July 28. She’s published hundreds of pieces before, but none have meant more than this one. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness signals her redemption.

A month later—seven months after her illness forced her to leave work—Susannah returns to her job at the Post. Human Resources advises her tostart off slowly, but she jumps in as if she never left. Unable to type as quickly as before, she records her interviews, her speech slow, plodding. Sometimes she slurs her words. Her coworkers discreetly edit her work, reeducating her in the basics of journalism. Susannah is convinced she’s back to normal, but in fact, she still has a long way to go before she returns to her former self.

Working on Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan

That afternoon, the Post’s Sunday editor asks Susannah if she’d be willing to write a first-person account of her illness. It’s the assignment Susannah has been hoping for.

She has four days to write Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan. She interviews Stephen, her family, and Drs. Najjar and Dalmau. She learns many things in the course of her research:

- Children make up 40 percent of those diagnosed with the disease.

- Many adults diagnosed with the disease were originally diagnosed with schizophrenia or autism.

- It’s cost-prohibitive to test all psychiatric patients for an autoimmune disease.

- Many doctors don’t keep abreast of current medical research.

The Post’s photo editor wants to illustrate Susannah’s article with images from the EEG videos taken during her stay in the hospital. Watching the videos, Susannah is frightened by seeing herself so unhinged, but she’s more frightened by the fact that emotions that once wracked her so completely have vanished entirely. The Susannah in the EEG video is a foreign entity to the Susannah writing about her own illness.

On October 4, Brain on Fire by Susannah Cahalan runs in the Post. She receives hundreds of emails from people who have the disease and want to know more about it. She even receives phone calls from people who want a diagnosis from Susannah herself. In a few months, Susannah feels comfortable in her own skin again.

Same But Different

Nevertheless, when Susannah compares pictures of herself taken before and after her illness, she notices that something has changed. In her everyday life, she notes subtle differences that indicate she’ll never be the same person she was before.

Sometimes memories from her month of oblivion rush back to her, knocking her off balance. With each memory recovered, she wonders what others remain, knowing there are thousands she’ll never retrieve. The other Susannah, the mad Susannah, calls out to her, saying, “Don’t forget me. Please.”

At one time, Susannah couldn’t answer yes to the question, “Would you take it all back if you could?” Today, she doesn’t regret her month of madness. Its darkness yielded too much light.

Brain On Fire Susannah Cahalan Summary

Besides writing Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, Susannah has shared her stories with universities, hospitals, and psychiatric institutions. She helped start the Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance, a nonprofit foundation fostering research and awareness of the illness.

———End of Preview———

Book Brain On Fire

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Susannah Cahalan's 'Brain On Fire' at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Brain On Fire summary:

- How a high-functioning reporter became virtually disabled within a matter of weeks

- How the author Cahalan recovered through a lengthy process and pieced together what happened to her

- How Cahalan's sickness reveals the many failures of the US healthcare system

NPR’s sites use cookies, similar tracking and storage technologies, and information about the device you use to access our sites (together, “cookies”) to enhance your viewing, listening and user experience, personalize content, personalize messages from NPR’s sponsors, provide social media features, and analyze NPR’s traffic. This information is shared with social media, sponsorship, analytics, and other vendors or service providers. See details.

You may click on “Your Choices” below to learn about and use cookie management tools to limit use of cookies when you visit NPR’s sites. You can adjust your cookie choices in those tools at any time. If you click “Agree and Continue” below, you acknowledge that your cookie choices in those tools will be respected and that you otherwise agree to the use of cookies on NPR’s sites.